Chapter 1: Preface

The gold mining industry has consistently held a unique and enduring position within the global economic system. Unlike most commodities, gold performs a dual function: it operates both as a productive industrial input and as a financial asset with intrinsic monetary value. This duality allows gold to remain resilient across economic cycles, serving simultaneously as a hedge against inflation, a store of value during financial crises, and a strategic reserve asset for governments and central banks. In periods of heightened geopolitical tension, currency depreciation, and market volatility, gold demand historically strengthens, reinforcing its role as a stabilizing force within the global financial architecture.

Beyond its financial significance, gold is an essential raw material for multiple downstream industries. It is widely used in jewelry manufacturing, which accounts for a substantial portion ofglobal demand, as well as in electronics, medical devices, aerospace components, and emerging green technologies. As technological sophistication increases, particularly in high-precision electronics and renewable energy systems, the industrial relevance of gold is expected to remain structurally strong over the long term.

Within this global framework, Indonesia occupies a strategically important position in the international gold mining industry. Indonesia is endowed with a vast and geologically diversemineral base, resulting from its location along the Pacific Ring of Fire. This tectonic setting has produced significant gold-bearing formations across the archipelago, enabling the country to host some of the largest and most economically viable gold deposits in the Asia-Pacific region.

Gold mineralization in Indonesia is distributed across several major islands and geological belts. Papua is home to world-class deposits associated with porphyry and epithermal systems, while Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Sulawesi contain extensive gold resources linked to volcanic arcs and sediment-hosted formations. This wide geographic distribution has allowed gold mining to contribute not only to national export earnings but also to regional economic development, particularly in remote and resource-dependent provinces.

Over the past two decades, Indonesia’s gold mining industry has undergone substantial transformation driven by regulatory reform, shifting investment patterns, and evolving national priorities. The gradual transition from long-term Contract of Work (CoW) arrangements to a licensing-based regime under Izin Usaha Pertambangan (IUP) and Izin Usaha Pertambangan Khusus (IUPK) reflects the government’s broader objective of strengthening state sovereignty over natural resources. These changes have altered ownership structures, increased state participation instrategic assets, and reshaped the risk-return profile for domestic and foreign investors alike.

At the same time, Indonesia has actively pursued a mineral downstreaming policy aimed at increasing domestic value addition. In the context of gold, this includes the development of refining capacity, bullion production, and integration with the domestic jewelry and precious metals industry.Downstreaming is intended to reduce reliance on raw material exports, stabilize export revenues, and enhance the multiplier effects of mining activities within the national economy.

Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations have become increasingly central to the operation of gold mining projects in Indonesia. Large- scale industrial mines are subject to comprehensive environmental impact assessments, reclamation guarantees, post-mining land use obligations, and community development programs. These requirements reflect both domestic regulatory evolution and growing international expectations regarding responsible sourcing and sustainable mining practices.

In parallel, artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) remains a structurally significant component of Indonesia’s gold sector. While ASGM provides livelihoods for hundreds of thousands of people, it also presents serious challenges related to environmental degradation, mercury pollution, occupational safety, and regulatory oversight. The coexistence of capital-intensive industrial mining operations and informal, community-based mining activities creates a dualistic industry structurethat is particularly pronounced in Indonesia compared to many developed mining jurisdictions.

From a macroeconomic standpoint, the gold mining industry contributes to Indonesia’seconomy through multiple channels. These include export earnings, tax and royalty payments, employment creation, infrastructure development, and regional fiscal transfers.

Gold production also supports downstream industries such as refining, minting, and jewelry manufacturing, thereby extending the value chain beyond extraction. However, the sector remains exposed to external variables such as global gold price fluctuations, exchange rate movements, and shifts in international investment sentiment, all of which directly influence exploration budgets, capital expenditure, and production planning.

Despite its substantial resource endowment, Indonesia’s gold mining industry faces persistent structural and operational challenges. Regulatory complexity across central and regional authorities, permitting delays, land access disputes, and social resistance in mining-affected communities can increase project risk and cost. Furthermore, the industry must adapt to global trends toward decarbonization, climate risk disclosure, and supply chain transparency, which increasingly influence investor decision-making and market access.

This report is designed to provide a comprehensive, structured, and data-driven analysis of the gold mining industry in Indonesia. It examines market size and trends, production and trade statistics, regional distribution networks, and the competitive landscape of major industry players.

In addition, it analyzes government policies, regulatory frameworks, and industry challenges, while benchmarking Indonesia’s gold mining practices against those of ASEAN countries, the European Union, and the United States. A SWOT analysis is included to systematically evaluate the industry’s internal strengths and weaknesses, as well as external opportunities and threats.

Chapter 2: Market Trends and Size of Gold Mining Industry in Indonesia

2.1 Structural Nature of the Gold Market

Unlike base metals or energy commodities, the gold market is structurally demand- inelastic and price-driven. This means that changes in price are influenced more by financial conditions and risk perception than by short-term supply–demand imbalances.

For gold-producing countries such as Indonesia, this structural characteristic has a direct implication: market size expansion is primarily driven by price appreciation rather than volume growth.

From 2020 to 2025, gold entered what can be described as a high-price structural regime, underpinned by:

- Persistently high global debt levels

- Inflation volatility and real interest rate uncertainty

- Geopolitical fragmentation and trade realignment

- Strategic diversification away from US dollar–centric reserves

This regime shift differentiates the 2020–2025 period from earlier commodity supercycles, where price increases were largely driven by industrial demand expansion.

2.2 Global Gold Price Cycle and Its Relevance to Indonesia

Gold prices moved from a cyclical commodity pattern into a macro-financial asset pattern during this period.

Implication for Indonesia:

In earlier cycles, Indonesian gold mining economics depended heavily on cost discipline and volume expansion. In the current regime, price leverage dominates, meaning that even stable production delivers outsized value gains.

2.3 Indonesia’s Gold Market Size: Multi-Dimensional View

To properly size Indonesia’s gold market, it is insufficient to rely on a single metric. A comprehensive view requires four complementary lenses:

1. Production Value (Primary Market Size)

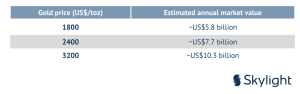

Indonesia produces approximately ~100 metric tons of gold annually, placing it among the top producers globally. At different gold price scenarios:

This demonstrates how price sensitivity outweighs tonnage growth in determining market size.

Annual Gold Production (Physical Volume)

- Indonesia’s gold production in 2023–2024 is consistently reported at around 100 metric tons per year (i.e., ~100,000 kg).

- Some government sources and officials have stated production figures ranging between 70–160 tonnes per year, depending on reporting methodology, mine performance, and inclusion of copper–gold co-products.

- Independent assessments put Indonesia’s production at around ~4% of global gold output, illustrating its significance in global mining.

Key takeaway (production):

Indonesia produces roughly 100 tonnes of gold annually, making it one of the world’s top gold producers.

2. Export Value (External Market Interface)

Indonesia’s gold export statistics show high volatility, not because of production instability, but due to:

- policy changes (export restrictions, downstreaming incentives),

- refining location decisions,

- stockpiling and internal transfers,

- changes in reporting and

Therefore, export value should be interpreted as policy- and structure-sensitive, not purely demand-driven.

- Based on customs statistics from BPS, Indonesia exported 76 tonnes of gold in 2024, with an export value of about US$1.06 billion.

- In early 2025, export revenues from gold reached about US$1.64 billion (January–September), showing growth driven by high global prices.

Key takeaway (exports):

The export market alone for Indonesian gold is over US$1 billion annually and could exceed US$1.6 billion when extended to full-year 2025.

3. Fiscal Market Size (Government Revenue Lens)

Gold mining contributes to the state through:

- royalties,

- corporate income tax,

- dividends from state participation,

- regional revenue sharing.

In a high-price environment, fiscal yield per ton increases disproportionately, strengthening the government’s incentive to maintain production continuity and regulatory stability.

4. Strategic Asset Market Size (Long-Term Value Lens)

Beyond annual cash flow, Indonesia’s gold market must be viewed as a strategic asset base, supported by:

- reserves exceeding 3,500 tons,

- long mine lives for major assets,

- optionality for future development under favorable policy and price conditions.

This long-term asset perspective is particularly relevant for sovereign planning and foreign direct investment (FDI) assessment.

2.4 Demand-Side Trends Shaping the Market

Although Indonesia is not a major end-consumption market, global demand composition directly influences its pricing power.

More than 65% of gold demand is non-industrial, making it less vulnerable to economic slowdowns compared to copper, nickel, or aluminum. This structural resilience benefits Indonesia as a producer.

Domestic demand includes jewelry, investment bars/coins, and other retail demand. According to industry analysis:

- Annual domestic gold demand (jewelry + investment) has been between ~37– 65 tonnes per year in recent years (2017–2022 data).

Key takeaway (domestic consumption): Indonesians consume tens of tonnes of gold per year, representing a significant segment of gold’s value chain beyond raw production and export.

2.5 Regional Market Dynamics: ASEAN and Asia-Pacific

Asia-Pacific has become the center of gravity for gold demand growth.

Key regional drivers:

- population growth and rising middle class,

- cultural affinity to physical gold,

- increasing retail investment platforms,

- proximity to major refining and trading hubs,

Within ASEAN, Indonesia stands out due to:

- scale of reserves,

- presence of world-class deposits,

- integrated mining–processing capabilities.

However, Indonesia competes with jurisdictions that often offer:

- faster permitting,

- clearer fiscal stability,

- more predictable land access frameworks.

This competition affects Indonesia’s ability to convert geological potential into market growth.

2.6 Indicative Market Size of Gold in Indonesia

To roughly estimate market size in value terms for annual Indonesian gold output:

- 100 tonnes of gold ≈ 100,000 kilograms.

- Gold price (recent level) ≈ US$4,000 per troy ounce (note: there are ~32,150 troy ounces per metric ton).

- One tonne equal ~32,150 troy ounces → 100 tonnes ≈ 3,215,000 troy ounces.

- 3,215,000 oz × US$4,000 ≈ US$12.86 billion per year (theoretical mine-gate value if all gold were valued at market price).

a. Scenario-Based Market Outlook (2025–2030) Scenario 1 – Base Case (Most Likely)

- Gold prices remain structurally high (US$2,400–3,000/toz).

- Indonesia production stable (~90–105 tons)

- Market size grows moderately via price leverage.

Scenario 2 – Upside Case

- Sustained geopolitical tension and central bank buying.

- New downstream/refining capacity improves export realization.

- Market value expands sharply without major volume increase.

Scenario 3 – Downside Case

- Global monetary tightening stabilizes inflation.

- Gold prices retreat but remain above historical averages.

- Indonesia market size contracts in value but remains profitable.

b. Key Market Trend Takeaways

- Indonesia’s gold market is price-driven, not volume-driven.

- High-price regimes materially expand market size without new mines.

- Export data alone underrepresents true market value.

- Policy certainty and ESG execution are now economic variables, not compliance issues.

- Long-term competitiveness depends on converting reserves into value under stable governance.

Chapter 3: Production, Export and Import Statistics

3.1 Scope, Methodology, and Interpretation Framework

This chapter consolidates production, export, and import statistics of Indonesia’s gold industry for the period 2020–2025, with the objective of explaining what happened, not merely listing numbers.

Three important methodological notes apply:

a. Production ≠ Exports

Gold mined in Indonesia is not automatically exported. It may be:

- refined domestically,

- stockpiled,

- sold to domestic buyers (banks, jewelry, state entities),

- reclassified under different trade forms.

b. Trade data reflects structure, not just demand

HS 7108 (non-monetary gold) captures flows, not necessarily origin of gold. Imports can coexist with high domestic production.

c. Balance interpretation must be qualitative

A “trade deficit” in HS 7108 does not imply economic weakness; it often reflects downstream activity, refining arbitrage, and policy effects.

3.2 Gold Mine Production in Indonesia (2020–2025)

3.2.1 Production Trend

Indonesia’s gold mine production shows a clear post-pandemic recovery followed by stabilization.

Table 3.1 – Indonesia Gold Mine Production

Key interpretation

- The 2020 dip reflects operational constraints and logistics

- The 2022 peak corresponds with normalization of large copper-gold operations.

- The 2023–2025 plateau indicates a mature production profile.

- Future growth is value-driven, not volume-

3.3 Export Performance (HS 7108 – Non-Monetary Gold)

3.3.1 Export Dynamics

Gold exports exhibit extreme volatility, primarily due to:

- downstreaming policy,

- refining location decisions,

- internal transfers,

- global price

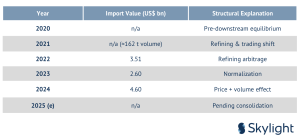

Table 3.2 – Indonesia Gold Exports

Export structure insight

- Singapore and Hong Kong dominate as

- Switzerland appears selectively as a refining

- Export decline does not track production decline, confirming structural effects.

3.4 Import Performance (HS 7108 – Non-Monetary Gold)

3.4.1 Import Surge Explained

Indonesia became a major gold importer under HS 7108 after 2021.

Table 3.3 – Indonesia Gold Imports

Major sources

- Hong Kong

- Australia

- Singapore

- Japan, UAE, Switzerland

Taken as a whole, the production, export, and import patterns observed between 2020 and 2025 confirm that Indonesia’s gold industry should be evaluated less as a conventional commodity sector and more as a strategic asset system.

Stable production around a long-term plateau indicates geological strength and operational maturity, while volatile trade flows reveal an industry actively adapting to policy shifts, downstream integration, and regional value-chain optimization.

For policymakers, this underscores the importance of regulatory consistency and transparent trade classification to avoid misinterpretation of sector performance. For investors and operators, the datasignals that future value creation will be driven not

by incremental tonnage growth, but by price leverage, operational efficiency, refining integration, and governance quality.

In this context, gold’s role in Indonesia extends beyond export revenue—it functions as a buffer against macroeconomic shocks, a contributor to fiscal resilience, and a platform for deeper participation in the Asia-Pacific precious metals ecosystem.

Chapter 4: Distribution Network of Gold Mining Industry

4.1 Conceptual Framework: Gold Distribution in an Archipelagic Economy

The distribution network of the gold mining industry in Indonesia is best understood as a spatial–economic system, rather than a linear supply chain. Indonesia’s archipelagic geography, uneven infrastructure development, and regionally differentiated regulatory enforcement create a gold distribution network that is multi- nodal, fragmented, and adaptive.

Gold does not move in a straight line from mine to market. Instead, it circulates through overlapping layers of extraction, aggregation, processing, consolidation, and financial settlement—often crossing provincial and international boundaries multiple times before reaching its final form.

4.2 National Gold Mining Map: Macro Spatial Distribution

At the national level, Indonesia’s gold mining activities are distributed across five primary spatial roles:

This geographic diversification provides system resilience—production disruption in one region rarely collapses national supply—but it simultaneously increases logistical complexity and governance costs.

4.3 Papua: Eastern Production Core and Structural Anchor

Papua is the single most important gold-producing region in Indonesia by volume and strategic weight. Gold here is predominantly produced as a co-product of large copper–gold porphyry systems, resulting in exceptionally high output concentration.

Distribution characteristics

- Highly centralized extraction

- Dedicated logistics corridors (mine → port)

- Maritime shipment to smelters/refiners

Economic implication

Papua acts as a stabilizing pillar for national gold supply. Its scale and infrastructure maturity reduce volatility in Indonesia’s aggregate production profile, even when smaller regions fluctuate.

4.4 Sumatra: Western Gold Corridors and Density Complexity

Sumatra represents the most complex gold distribution environment in Indonesia. Gold deposits are widely spread along volcanic belts, creating numerous extraction and aggregation points.

Key spatial features

- High interaction between industrial mining and ASGM

- Proximity to ports and population centers

- Multiple informal-to-formal transition nodes

Economic trade-off

- High accessibility and liquidity

- Elevated traceability and ESG risks

Sumatra functions as a high-velocity gold corridor, where governance quality directly determines whether gold flows enhance national value capture or leak into informal channels.

4.5 Kalimantan: Inland Gold and River-Based Distribution

Kalimantan illustrates the logistical friction inherent in Indonesia’s gold network.

Many gold deposits are located deep inland, far from ports and urban centers.

Distribution structure

- River transport as primary logistics backbone

- Late-stage formalization of gold flows

- High environmental exposure

Strategic implication

Kalimantan converts geological wealth into higher distribution cost per ounce, reducing net economic efficiency unless infrastructure and formalization improve.

4.6 Sulawesi: Emerging Integrated Growth Node

Sulawesi is transitioning into an emerging gold distribution node, benefiting from infrastructure spillovers from other mining sectors.

Drivers

- New ports and power infrastructure

- Industrial zoning

- Increasing investor interest

Sulawesi has the potential to become a midstream optimization hub, reducing dependency on western export gateways.

4.7 Java: Control, Refining, and Demand Center

Java is not a mining center, but it is the economic command center of Indonesia’s gold distribution system.

Roles

- Corporate HQs & regulators

- Financial settlement & bullion trading

- Jewelry manufacturing & consumption

Java is where physical gold is converted into economic value.

4.8 End-to-End Gold Flow Architecture Integrated flow

- Mining (regional)

- Aggregation (formal & informal)

- Primary processing

- Inter-island transport

- Refining & consolidation

- Domestic absorption or export

Each node represents a value, risk, and governance transformation point.

4.9 Strategic Interpretation: Distribution as a Competitive Variable

- Resilience vs efficiency: decentralization increases resilience but raises

- Traceability = market access: ESG compliance affects financing and

- Refining capacity = value retention: domestic refining shortens chains and stabilizes trade data.

In modern gold markets, distribution efficiency is as valuable as ore grade.

4.10 Chapter 4 Key Takeaways

- Indonesia’s gold network is geographically diversified but operationally fragmented.

- Papua anchors volume: Sumatra and Kalimantan define complexity; Sulawesi offers optimization; Java controls value realization.

- Logistics and governance—not geology—are the main constraints on

- Strengthening distribution yields higher returns than marginal production

Chapter 5: Major Players in the Industry

5.1 Strategic Context: Why “Major Players” Matter More Than Market Share

In Indonesia, identifying major players in the gold mining industry is not merely an exercise in ranking production volumes. Due to the country’s resource nationalism framework, downstream policy orientation, and geological structure, the strategic importance of a company is determined by a combination of:

- Control over Tier-1 or long-life assets

- Ability to operate under Indonesia’s regulatory and ESG regime

- Alignment with national ownership and downstream objectives

- Access to capital, technology, and processing infrastructure

As a result, Indonesia’s gold industry is hierarchical rather than fragmented. A small number ofanchor producers dominate national output, while a broader layer of mid-tier and growth-oriented players contribute incremental supply, regional development, and future optionality.

From a policy and investment perspective, this structure means that systemic risk is concentrated, but so is systemic stability.

5.2 Industry Segmentation: Three Strategic Layers

Indonesia’s gold mining players can be grouped into three functional layers:

Layer 1 – Anchor Producers (System Stabilizers)

These are large-scale copper–gold or flagship gold operations whose output materially affects national production, exports, and fiscal revenues.

Layer 2 – Primary & Mid-Tier Gold Producers

These companies’ economics are primarily gold driven. They are more sensitive to operational efficiency, permitting continuity, and cost inflation.

Layer 3 – Strategic Downstream & Ecosystem Players

These entities do not necessarily dominate mining output but are critical for refining, bullion trust, domestic liquidity, and formal market development.

5.3 In-Depth Analysis of Key Players

Anchor Producers: Structural Pillars of Supply

1. PT Freeport Indonesia

PT Freeport Indonesia (PTFI) is the single most influential gold producer in the country. Operating the Grasberg district in Papua, PTFI produces gold predominantly as a by-product of copper mining.

Status: MIXED – STATE MAJORITY, FOREIGN ORIGIN & OPERATIONS

- Legal entity: Indonesian (PT)

- Majority economic ownership: Indonesian state (via MIND ID / Inalum)

- Operational origin & technical control: Freeport-McMoRan (USA)

- Foreign exposure: Very high (technology, mine planning legacy, management systems)

- Country of foreign origin: United States

Analytical significance

- Anchors Indonesia’s gold supply curve

- Extremely long reserve life and high capital intensity

- Gold output is relatively insulated from short-term price volatility

Strategic interpretation

PTFI ensures production continuity and fiscal stability, making it a cornerstone of Indonesia’s mining economy rather than a conventional gold company.

2. PT Amman Mineral

PT Amman Mineral operates the Batu Hijau mine and represents Indonesia’s second anchor producer.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, FOREIGN CAPITAL PRESENT

- Legal entity: Indonesian public company

- Controlling shareholders: PT Sumber Gemilang Persada & PT Medco Energi (Indonesia)

- Foreign exposure:

- Foreign institutional investors (public float)

- International lenders / bondholders

- No foreign operator control

- Domestic-controlled with foreign portfolio capital

- Country of foreign origin (capital only): Multiple (portfolio investors)

Analytical significance

- Large and stable gold output

- Increasing domestic ownership and governance integration

- Key contributor to eastern Indonesia’s mining logistics

Strategic interpretation

Amman Mineral reflects Indonesia’s post-divestment model: domestically anchored ownership combined with global-scale operations.

Primary and Mid-Tier Gold Producers: Value Creators and Risk Bearers

3. PT Agincourt Resources

Operator of the Martabe mine in North Sumatra, Agincourt represents

Indonesia’s benchmark primary gold operation.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, HISTORICALLY FOREIGN

- Legal entity: Indonesian (PT)

- Ownership:

- 95% Danusa Tambang Nusantara (Astra Group – Indonesia)

- 5% Local government

- Foreign exposure:

- No controlling foreign equity

- Some foreign contractors & suppliers only

- Fully domestic-controlled

- Country of foreign origin: None (current)

Why it matters

- Pure gold economics (minimal copper influence)

- High operational discipline and cost control

- Strong integration with local government stakeholders

- PT Merdeka Copper Gold Tbk

Merdeka Copper Gold is a growth-platform miner, with gold from Tujuh Bukit forming an increasingly important revenue stream.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, FOREIGN FINANCING MATERIAL

- Legal entity: Indonesian public company

- Controlling shareholders: Indonesian founders & domestic institutions

- Foreign exposure:

- Foreign institutional investors (public float)

- International project finance, streaming, and bonds

- MDKA is not foreign-controlled, but foreign capital is strategically important.

- Domestic-controlled with significant foreign financing

- Country of foreign origin: Multiple (capital markets)

Analytical significance

- Strong project pipeline and capital-market access

- Transitioning from mid-tier to upper-tier status

- Higher execution risk, but higher upside optionality

5. PT J Resources Asia Pasifik Tbk

J Resources operates multiple gold assets and exemplifies a portfolio-based gold producer.

Status: MIXED – INDONESIAN ENTITY WITH FOREIGN CONTROLLING LINEAGE

- Legal entity: Indonesian public company

- Ownership:

- Historically linked to foreign-based groups (Japan / Hong Kong lineage via earlier ownership chains)

- Current disclosures show Indonesian legal control, but capital lineage remains mixed

- Foreign exposure:

- Legacy foreign shareholders

- Offshore holding structures

- Mixed ownership (domestic legal entity, foreign lineage capital)

- Country of foreign origin: Japan / Hong Kong (historical capital lineage)

Analytical significance

- Asset diversification reduces single-mine risk

- Moderate scale limits pricing power

- Sensitive to regulatory and operational disruptions

6. PT Archi Indonesia Tbk

Archi Indonesia operates the Toka Tindung mine and illustrates the operational fragility of mid-tier gold miners.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, FOREIGN ORIGIN ASSET

- Legal entity: Indonesian public company

- Controlling shareholder: Indonesian entity

- Foreign exposure:

- Asset originally developed by foreign junior miners

- Current ownership largely domestic + foreign portfolio investors

- Domestic-controlled with foreign-origin asset & portfolio capital

- Country of foreign origin (asset origin): Australia (historical)

Key insight

- Small operational shocks can materially affect output

- Sustaining capital and grade control are critical

- PT Bumi Resources Minerals Tbk

BRMS represents the scaling segment of Indonesia’s gold industry.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, CAPITAL-MARKET DEPENDENT

- Legal entity: Indonesian public company

- Controlling shareholder: Indonesian group

- Foreign exposure:

- Foreign investors via bonds & equity

- No foreign operational control

- Domestic-controlled with foreign portfolio capital

- Country of foreign origin: Multiple (portfolio)

Analytical significance

- Rapid growth from a low base

- Capital-market dependent

- Execution quality determines long-term viability

8. PT Nusa Halmahera Minerals

Operator of the Gosowong underground mine, NHM is a legacy asset operator.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, FORMERLY FOREIGN

- Legal entity: Indonesian (PT)

- Current ownership: Indotan Group (Indonesia)

- Historical ownership:

- Newcrest Mining (Australia)

- Foreign exposure: minimal currently

- Fully domestic-controlled (post-acquisition)

- Country of foreign origin (historical): Australia

Strategic insight

- Underground complexity raises costs

- Asset recycling into domestic ownership highlights industry maturation

Downstream and Ecosystem Players

9. PT United Tractors Tbk

United Tractors participates in gold primarily as a portfolio diversifier.

Status: DOMESTIC-CONTROLLED, FOREIGN CAPITAL PASSIVE

- Legal entity: Indonesian public company

- Controlling shareholder: Astra International (Indonesia/Singapore holding)

- Foreign exposure:

- Astra has foreign institutional shareholders

- No foreign operational control

- Domestic-controlled with foreign passive capital

- Country of foreign origin: None (control)

Analytical significance

- Gold provides cash-flow stability

- Institutional governance raises industry standards

10. PT Aneka Tambang Tbk

ANTAM, particularly through Logam Mulia, is Indonesia’s bullion and refining backbone.

Status: FULLY DOMESTIC – STATE-OWNED

- Legal entity: Indonesian SOE

- Ownership: Indonesian state (via MIND ID)

- Foreign exposure:

- None in equity

- Only technology / certification interfaces (LBMA)

- Fully domestic state-owned

- Country of foreign origin: None

Strategic importance

- Enables formal gold markets

- Supports downstream policy and retail investment

- Trust and accreditation role exceeds mining output significance

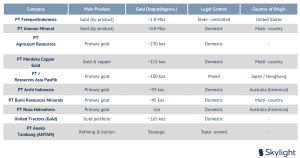

5.4 Summary Table – Major Gold Industry Players in Indonesia Table 5.1 – Top Players Overview

5.5 Strategic Synthesis of Chapter 5

Several structural conclusions emerge from this analysis:

- Indonesia’s gold industry is highly concentrated at the top, with two anchor producers stabilizing the entire system.

- Domestic ownership now dominates, reflecting successful resource- nationalism objectives.

- Mid-tier miners carry disproportionate operational and regulatory risk, making execution quality decisive.

- Downstream and trust infrastructure are strategic assets, not ancillary activities.

- Future leadership in Indonesia’s gold sector will depend less on geology and more on capital strength, governance, policy alignment, and ESG credibility.

Chapter 6: Major Players in the Industry

6.1 Policy Direction (2020–2025): What the Government Is Trying to Achieve

Indonesia’s gold mining governance in 2020–2025 can be summarized as a coordinated push toward (i) stronger state control and licensing certainty, (ii) downstream value-add and reduced raw export dependence, and (iii) tighter ESG/environmental compliance, while simultaneously attempting to simplify investment procedures through omnibus reforms and digital licensing.

Three policy goals consistently appear across the reform stack:

- Resource governance & state leverage: strengthen national control over strategic minerals via clearer permit structures and central authority.

- Downstreaming (domestic processing): shift from exporting raw mineral products toward domestic smelting/refining and higher value capture; enforcement has been most visible in concentrate export policy.

- Regulatory streamlining & risk-based licensing: consolidate and standardize licensing throughOnline Single Submission (OSS) and risk-based business licensing.

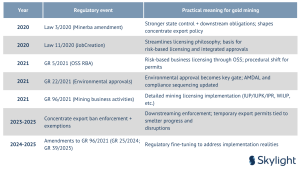

6.2 Key Legal and Regulatory Framework (Core Instruments)

6.2.1 Mining Law Reform Backbone

-

- Law No. 3 of 2020 (amending Law No. 4/2009 on Minerals and Coal / “Minerba”) is a cornerstone reform for mining governance, setting the foundation for licensing, contract conversion, and downstream obligations.

- Law 11 of 2020 (“Job Creation / Omnibus Law”) introduced broad reforms to streamline business licensing and investment across sectors, including mining-related permitting logic.

Implementing Regulations for Mining Operations

- Government Regulation (GR) No. 96/2021 (“Implementation of Mineral and Coal Mining Business Activities”) operationalizes the mining business licensing regime (IUP/IUPK/IPR), mining area concepts, and operational requirements.

- GR 96/2021 has been subsequently amended (including GR 25/2024 and GR 39/2025) showing active regulatory iteration to adjust to implementation needs.

6.2.3 Risk-Based Licensing (OSS-RBA)

- GR No. 5/2021 establishes the risk-based licensing framework under OSS (“OSS RBA”), shifting licensing requirements based on risk classification and standardized approvals.

6.2.4 Environmental Approval and Compliance

- GR No. 22/2021 restructures environmental governance by emphasizing environmental approval (persetujuan lingkungan) as a prerequisite for business activities with environmental impacts, including mining.

- The framework has continued to be refined through administrative delegation and process streamlining (e.g., delegation-related updates in 2024 to support implementation).

6.3 Regulatory Timeline (2020–2025): How the Rules Evolved Figure 6.1 — Timeline of major regulatory milestones

6.4 Downstreaming and Export Policy: Why It Matters Even for Gold

Even though gold can be produced as doré or refined bullion, Indonesia’s downstream policy pressure has been most visible through copper concentrate export restrictions that affect copper–gold producers (the largest gold contributors nationally).

6.4.1 Concentrate export restrictions and deadlines

Freeport publicly referenced Article 170A of the Minerba Law framework as setting a deadline for concentrate exports to cease by June 2023 (three years after the law came into force), indicating how downstreaming obligations were operationalized for copper concentrates—indirectly shaping gold co-product flows.

6.4.2 Exemptions, transitional permits, and the “smelter-linked” logic

Reuters reporting shows Indonesia implemented a ban in June 2023 but granted exemptions to certain firms (notably Freeport and Amman) linked to smelter completion timelines and later discussed extensions and levies.

6.4.3 Operational disruptions and policy flexibility (2024–2025)

In 2025, Reuters reported a temporary export permit for Freeport tied to smelter repair needs after a fire, explicitly justified as maintaining royalties during downtime—while also noting the commissioning of a precious metal’s refinery in Gresik that processes gold and other precious metals. Reuters also reported policy debate around allowing Amman to export copper concentrate amid local economic impacts and smelter ramp-up issues.

Why this matters for the gold chapter:

Indonesia’s gold “system” is heavily influenced by copper–gold majors. When concentrate export policy tightens or relaxes, it impacts production scheduling, stockpiles, processing throughput, and the timing/route of gold recovery and refining—even if gold itself is not the formal policy target.

6.5 Artisanal and Small-Scale Gold Mining (ASGM): Regulation vs Enforcement Reality

ASGM is a defining governance challenge for Indonesia’s gold sector because it intersectsenvironmental health, legality, rural livelihoods, and supply-chain traceability.

6.5.1 Mercury and Minamata compliance framework

Indonesia has formal commitments to mercury reduction under Minamata and published national action planning documents addressing mercury in ASGM.

Academic and policy research consistently identifies mercury use in ASGM as a major environmental and public health risk that is difficult to eliminate without coordinated enforcement, alternative livelihood pathways, and formalization incentives.

6.5.2 People’s mining management and formalization intent

Government communications emphasize strengthening and expanding frameworks for people’s mining areas (WPR) and related governance—reflecting a policy intent to bring small-scale mining into a more manageable legal structure.

6.5.3 Persistent enforcement and traceability gap

Even with formal rules, the compliance gap remains a structural risk for Indonesia’s gold reputation and responsible sourcing alignment. Environmental reporting and investigations continue to highlight how illegal mining and mercury pollution can persist where enforcement is weak (this remains relevant beyond 2025 as well).

6.6 Key Regulatory Challenges (What Actually Makes Projects Slow or Risky)

6.6.1 Licensing complexity and administrative coordination

While OSS RBA aims to streamline licensing, mining projects still face complexity due to:

- multi-layer approvals (central and regional),

- land access issues,

- overlapping spatial planning (forestry, conservation, community land),

- sequential dependencies between mining permits and environmental approval.

6.6.2 Environmental and social permitting as a “project schedule driver”

Under the post-2021 framework, environmental approval becomes a central gate. Mining companies must treat AMDAL/permitting not as paperwork but as a critical path item that can determine the feasibility timeline.

6.6.3 Downstream obligations and infrastructure execution risk

Downstreaming policy effectiveness depends on smelter/refinery execution. Delays, technical issues, or disruptions can lead to:

- stockpiling,

- reduced mine throughput,

- requests for temporary export flexibility,

- policy uncertainty for investment planning.

6.6.4 ESG, responsible sourcing, and market access

As global bullion markets tighten responsible sourcing expectations, reputational risks from ASGM-linked mercury issues or traceability weaknesses can translate into:

- discounting,

- restricted market access,

- higher financing costs (especially for growth miners)

6.7 “Regulatory Risk Map” (Practical View for Investors and Operators)

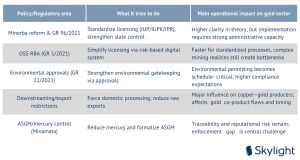

Table 6.2 — Policy area vs operational impact (2020–2025)

6.8 Chapter 6 Key Takeaways

- Indonesia’s 2020–2025 reforms moved in two directions at once: simplify licensing (OSS-RBA) while strengthening environmental and downstream compliance gates.

- Downstreaming policy materially affects gold, because the dominant producers are copper–gold systems and their throughput is tied to concentrate/export and smelter readiness.

- ASGM remains the largest governance risk for Indonesia’s gold reputation due to mercury, legality, and traceability—policy exists, but implementation is

- Regulatory iteration is ongoing, shown by amendments to GR 96/2021 through 2024–2025—important for investor certainty and project planning.

Chapter 7: Benchmark / Common & Best Practices

7.1 Why Benchmarking Is Important

Benchmarking helps answer a very practical question: If Indonesia sells gold into the same global market as other countries, how competitive and trusted is Indonesian gold compared to others?

From previous chapters, Indonesia is known best for the:

- has large and long-life gold resources (Chapter 2–3),

- has strong domestic ownership of major mines (Chapter 5),

- but faces logistical, traceability, and policy challenges (Chapter 4 & 6).

This chapter compares Indonesia with:

- ASEAN neighbors (regional competition),

- Europe (rule-setter and buyer benchmark),

- Australia (best-practice mining country),

- United States (stability and trust benchmark).

7.2 ASEAN Comparison: Indonesia vs Regional Neighbors Gold Mining Reality in ASEAN

ASEAN countries vary widely in geology, regulation, and mining maturity. Indonesia stands out clearly in scale, but not always in simplicity.

Table 7.1 — ASEAN Gold Mining Comparison

Interpretation (ASEAN):

- Indonesia dominates by volume and resource quality.

- Smaller ASEAN producers benefit from simpler governance but lack scale

- Indonesia’s challenge is managing complexity at scale, not competing on output

7.3 European Comparison: Producer vs Rule-Setter Gold Mining in Europe (Big Rules, Small Output)

Europe is not a major gold producer, but it strongly influences:

- how gold must be sourced,

- how it must be documented,

- which gold is accepted by banks and

Table 7.2 — Europe Gold Mining & Market Benchmark

Interpretation (Europe):

- Europe sets the rules of acceptance, not

- Indonesian gold must meet European expectations to avoid price discounts or

- Even small compliance gaps matter more than

7.4 Indonesia vs Australia: Best-Practice Benchmark

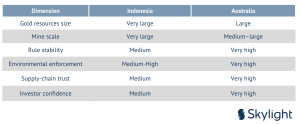

Australia is often considered the gold standard of gold mining.

Table 7.3 — Indonesia vs Australia

Key lesson from Australia:

Trust, rule stability, and consistency can create more value than bigger deposits.

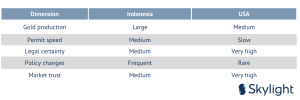

7.5 Indonesia vs United States: Stability Benchmark

The United States focuses on legal certainty rather than speed.

Table 7.4 — Indonesia vs United States

Interpretation:

Indonesia’s advantage is geology; the US advantage is predictability.

7.6 SWOT Analysis — Indonesia Gold Mining Industry SWOT Matrix

7.7 Key Conclusions from the Benchmark

- Indonesia leads ASEAN in gold resources and production by a wide margin.

- Australia is the closest real benchmark for best mining practice, not because of volume, but because of trust and stability.

- Europe and the USA control acceptance standards, even though they produce less gold.

- Indonesia’s main weakness is not geology, but consistency and traceability.

- The fastest competitiveness gains come from:

- clearer and steadier rules,

- stronger supply-chain documentation,

- better alignment with global buyer

Chapter 8: Writer’s Opinion

Based on the writing presented in Chapters 1–7, Indonesia’s gold mining industry has reached a structural turning point. The country has already achieved what many resource-rich nations aspire to: control over world-class gold assets, long mine life, and regional dominance within ASEAN. However, the next phase of value creation will not come from discovering more gold or producing significantly higher volumes. It will come from how Indonesia manages trust, consistency, and integration with global markets. In simple terms, Indonesia has already won the “geology game”. The challenge ahead is winning the “system game.”

8.2 What Indonesia Is Doing Right

From a strategic perspective, there are several areas where Indonesia is clearly moving in the right direction.

1. Strong Domestic Control Over Strategic Assets

Indonesia’s shift toward domestic and state-linked ownership of major gold assets has significantly reduced sovereign risk. Compared to a decade ago, the country now has:

- greater bargaining power,

- stronger alignment between mining operations and national interests,

- better ability to capture long-term

This is a major structural strength that should not be underestimated.

2. Anchor Producers Provide Stability

Large copper–gold systems act as shock absorbers for the national gold industry. Even when:

- gold prices fluctuate,

- smaller operators struggle,

- regulations are adjusted; national output remains stable. This gives Indonesia a level of resilience that many smaller gold-producing countries lack.

3. Clear Policy Intent Toward Downstream Value

Although execution is uneven, the direction is clear: Indonesia wants gold to generate value inside the country, not only at the mine gate. Domestic refining, bullion markets, and financial products linked to gold are logical extensions of this vision.

8.3 Where Indonesia Is Still Losing Value

Despite these strengths, Indonesia is still leaking value in several critical areas.

1. Inconsistent Policy Signals

From an investor and operator perspective, the biggest concern is not regulation itself, but frequent adjustment and uncertainty. Even well-intended policies can:

- delay investment,

- increase financing costs,

- push capital toward safer jurisdictions like Australia or the United Consistency matters more than strictness.

2. Traceability and Informal Mining Remain a Reputation Risk

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining is not unique to Indonesia, but its scale and visibility create disproportionate reputational risk. In global gold markets:

- one weak link can affect the entire chain,

- buyers and refiners increasingly apply “zero tolerance”

As long as traceability remains uneven, Indonesian gold will continue to face:

- price discounts,

- additional scrutiny,

- or slower access to premium markets.

3. Logistics and Geography Are Structural Constraints

Indonesia’s geography will never change. The country must therefore over-invest in coordination, digital tracking, and governance, simply to reach the same efficiency level as land-based mining nations.

8.4 Lessons from Australia, Europe, and the United States

The benchmark comparisons in Chapter 7 offer a clear lesson:

Countries with less gold often earn more trust—and therefore more value— than countries with more gold.

- Australia proves that stable rules and high transparency reduce financing costs and attract long-term capital.

- Europe shows that buyers and regulators, not producers, increasingly decide what gold is acceptable.

- The United States demonstrates that predictability—even when slow— creates confidence.

Indonesia does not need to copy these systems wholesale, but it must internalize the logic behind them.

8.5 What Will Define Indonesia’s Gold Industry in the Next 10 Years

In the writer’s view, Indonesia’s gold industry will be shaped by five decisive factors:

- Rule stability: Fewer changes, clearer timelines, stronger coordination between

- Trust infrastructure: Traceability systems, refinery credibility, and documentation quality will matter as much as production volume.

- ASGM formalization: Not as a social project alone, but as a market–access strategy.

- Domestic value chains: Gold should increasingly circulate within Indonesia—through refining, finance, and investment products—before export.

- Global alignment without loss of sovereignty: Indonesia can remain domestically controlled while fully aligned with global standards. These are not contradictory goals.

8.6 Final Opinion

Indonesia does not need to become the world’s largest gold producer to succeed. It already has enough gold. What it needs is to become:

- more predictable,

- more trusted, and

- more integrated with global expectations, while maintaining national control over its resources.

If Indonesia succeeds in this transition, its gold industry will not only be large—it will be globally respected, financially efficient, and strategically powerful.

Chapter 9: Conclusion

9.1 Indonesia’s Gold Industry in One View

This report set out to provide a complete, practical picture of Indonesia’s gold mining industry—from market size and production trends to distribution networks, major players, policy direction, and international benchmarks. When viewed as a whole, one conclusion stands out clearly:

Indonesia is already a gold powerhouse by resources and production, but its future value depends far more on systems, trust, and consistency than on discovering new gold. Indonesia’s gold sector is nolonger in an early development

phase. It has entered a mature stage, where stability, governance quality, and integration with global markets define success.

9.2 Market and Production: Strong but Mature

From the analysis in Chapters 2 and 3, Indonesia’s gold industry shows:

- Large and stable production, supported by long-life, world-class deposits

- Limited upside from volume growth, as most major assets are already in steady operation

- Strong sensitivity to gold prices, meaning value growth is mainly price- driven, not tonnage-driven

This profile places Indonesia alongside established mining jurisdictions rather than emerging producers. As a result, future performance should be measured not by how much more gold is mined, but by how efficiently and credibly that gold is monetized.

9.3 Distribution and Structure: Resilient but Complex

Indonesia’s archipelagic geography creates a highly diversified but fragmented distribution network (Chapter 4). This structure has two important consequences:

- Resilience: Disruptions in one region rarely halt national output, thanks to geographic spread and multiple production centers.

- Complexity and Cost: Logistics, coordination, and oversight are more expensive and more difficult than in land-based mining countries.

This means Indonesia must rely more heavily on:

- strong coordination,

- clear rules,

- digital tracking and documentation,

This could achieve the same level of efficiency and trust as simpler jurisdictions.

9.4 Industry Players: Domestic Control with Global Exposure

Chapter 5 demonstrated that Indonesia’s gold industry is now largely domestically controlled, particularly at the asset and license level. This represents a major strategic shift compared to the past. At the same time: foreign capital, global technology, and international market standards remain deeply embedded in the system. This hybrid model—domestic control with global integration—is not a weakness. It is, in fact, a realistic and sustainable structure for a major resource economy. The key risk lies not in foreign involvement, but in misalignment between domestic policy execution and global expectations.

9.5 Policy and Regulation: Clear Direction, Uneven Execution

Government policy (Chapter 6) shows a consistent direction:

- stronger state control,

- downstream value addition,

- higher environmental and social standards.

However, the analysis also shows that:

- frequent adjustments,

- transitional exemptions,

- and coordination challenges

can reduce predictability for operators and investors. In a mature gold industry, predictability often matters more than generosity. Clear timelines and consistent enforcement create more value than short-term flexibility.

9.6 Benchmarking Results: Where Indonesia Truly Stands

The benchmark analysis in Chapter 7 highlights a crucial insight:

- Indonesia outperforms ASEAN peers by scale and resources

- Australia outperforms Indonesia in trust, consistency, and investor confidence

- Europe and the United States, despite smaller production, shape market acceptance standards

This means Indonesia competes in two arenas at once:

- As a producer, where it is already strong

- As a trusted supplier, where there is still room to improve

Sources

- Skylight Analytics Hub

- Government of Law No. 4 of 2009 on Mineral and Coal Mining (Minerba Law).

- Government of Law No. 3 of 2020 concerning Amendments to Law No. 4/2009 on Mineral and Coal Mining.

- Government of Law No. 11 of 2020 on Job Creation (Omnibus Law).

- Government of Government Regulation No. 5 of 2021 on Risk-Based Business Licensing.

- Government of Government Regulation No. 22 of 2021 on Environmental Protection and Management.

- Government of Government Regulation No. 96 of 2021 on the Implementation of Mineral and Coal Mining Business Activities.

- Government of Indonesia. Government Regulation No. 25 of 2024 (Amendment to GR 96/2021).

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR). Mineral and Coal Statistics (Annual Editions, 2020–2024).

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR). Annual Mining Performance

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. Natural Resource Revenue and Fiscal Contribution Reports.

- PT Freeport Annual Report and Sustainability Report.

- PT Amman Mineral Internasional Annual Report and Investor Presentations.

- PT Agincourt Martabe Mine Sustainability and Production Reports.

- PT Merdeka Copper Gold Annual Report and Technical Disclosures.

- PT J Resources Asia Pasifik Annual and Quarterly Reports.

- PT Archi Indonesia Annual Report and Operational Updates.

- PT Bumi Resources Minerals Annual Report and Production Statements.

- PT Nusa Halmahera Corporate and Environmental Reports.

- PT United Tractors Annual Report (Mining and Gold Segment).

- PT Aneka Tambang Tbk (ANTAM). Annual Report and Logam Mulia

- World Gold Gold Demand Trends (Quarterly and Annual Editions).

- World Gold Responsible Gold Mining Principles.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). Commodity Market

- World Mining Sector and Minerals Development Reports.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). OECD GoldSupplement to the Due Diligence Guidance.

- Indonesia Mining Policy and Gold Industry Coverage (2020–2025).

- Global Gold Market and Mining Industry Analysis.

- S&P Global Commodity Gold Mining and Metals Industry Reports